Waiting for the Impossible Resolution

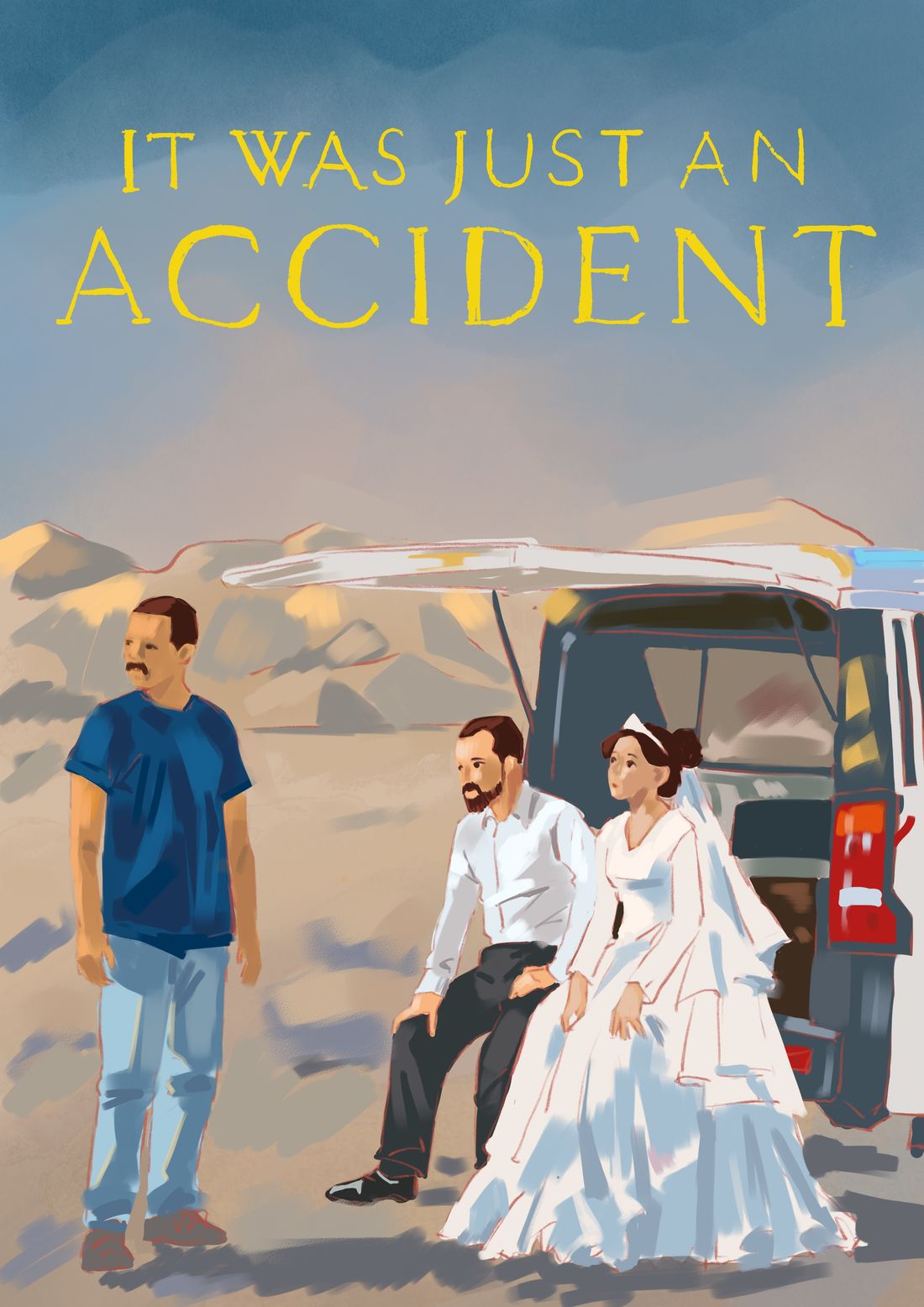

In It Was Just An Accident, Jafar Panahi spins an existential web around one man’s metal leg.

Reading Time: 3 minutes

About halfway through Jafar Panahi’s film It Was Just An Accident (2025), the hot-headed Hamid (Mohamad Ali Elyasmehr) addresses his ex-partner Shiva (Mariam Afshari) as she slumps under the weak shade of a tree. The two of them, along with a bride and groom and a middle-aged auto mechanic, have kidnapped a man (Ebrahim Azizi) whom they believe to be Eghbal, their brutal torturer in political prison. The plan was to bury Eghbal alive, except for a thorn in their sides—it is not entirely clear whether this man, who pleads his innocence, is Eghbal at all.

Gesturing at their predicament, Hamid muses to Shiva that he is reminded of Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot (1953). In the play, two men wait by the side of the road for an obscure figure named Godot to jumpstart their lives. It Was Just An Accident mirrors this situation, conveying the desperate feeling of waiting and wondering while time continues to fly by.

In an opening structurally similar to Psycho (1960), It Was Just An Accident, which won the 2025 Palme d’Or at Cannes, begins by following the kidnapped man, a character who will spend the majority of the film’s runtime knocked out and/or tied up.

The kidnapped man drives down a road with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The car breaks down, and Azizi pulls into an auto-shop, where the sound of his prosthetic gait is recognized by Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri) as belonging to his torturer Eghbal, who had lost his leg in Syria. The next day, Vahid tracks down Azizi and kidnaps him, tying him up in the back of his large white van.

Vahid drives to a rural desert area, where he is about to kill Azizi, before he begins to doubt his prior assessment that this man is truly Eghbal. The narrative then follows Vahid enlisting the help of Eghbal’s other victims (Mohamad Ali Elyasmehr, Mariam Afshari, and Hadis Pakbaten) to determine whether Azizi is the cruel prison guard they believe he is, or simply a husband and father with an unfortunate prosthetic limb.

Jafar Panahi has personal experience with Iran’s morality police, the law enforcement arm of Iran’s fundamentalist Islamic Regime, and political detention, having been arrested in 2010 after attempting to film a documentary about the contested 2009 re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, released from jail after a hunger strike a month later, and then being placed under house arrest for six years. It Was Just An Accident faced legal troubles within Iran as well: the movie was filmed without permission from the Islamic Republic, and included scenes where women appeared without the compulsory hijabs. In December 2025, the Iranian government sentenced Panahi to another year of prison for “creating propaganda against the political system.”

His portrayal of Vahid’s situation provides a reflecting glass for Panahi to sort through his obvious trauma, investigating a revenge fantasy. What would you do if you came face-to-face with the man who ruined your life? And, more importantly, what would you do if you ended up temporarily responsible for his wife and daughter?

Aside from being a dramatic psychological thriller, It Was Just An Accident also plays like a buddy comedy, as if Superbad (2007) was set in a gulag. The comedic aspects of the film, such as when a police officer asks for a tip after accepting a bribe, all serve to drive home the level of absurdity that life under the morality police is.

The subject matter is dark, and the movie is close to two hours long, but the plot never drags with its emotionally charged silences and satiric elements. Panahi spins an existential web around one man’s metal leg.

What, exactly, was just an accident? The plot is a series of accidents and circumstances, each of which creates new potholes for the characters to fall through and morally fail. Does this man’s accident entitle me to my accident, and how can we dig ourselves out of the mire of these cascading accidents? In some ways, Panahi argues, the original sin of the morality police has been committed, and the rest doesn’t matter.