The Four Letters I Keep Repeating

My four-letter name has never been long, yet somehow it’s always been too unfamiliar for the world to say without stumbling.

Reading Time: 7 minutes

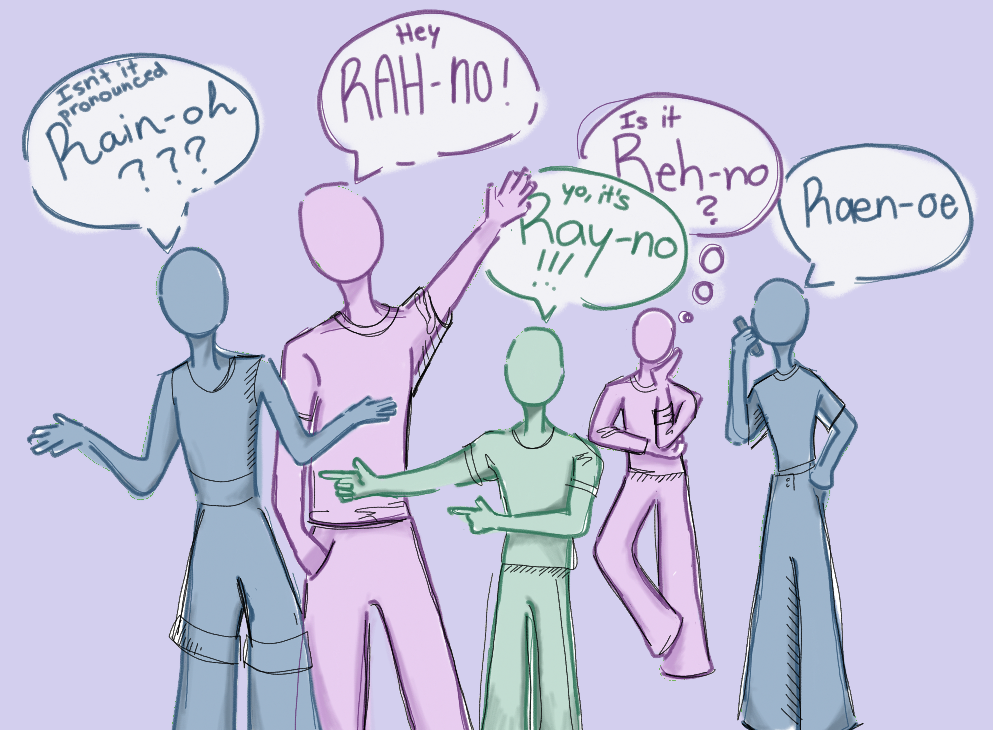

Ran-o. Rain-o. Ran. Rowa. And my personal favorite, Rhino. These are only a few of the names I’ve been called over the years by teachers, friends, classmates, and strangers alike.

My name, “Rano,” is short—shorter than most in every class I’ve ever been in. Yet, it carries weight far greater than its size. In Uzbekistan, it’s the name of a mystical flower no human has ever seen. In Uzbek, it’s associated with elegance, grace, and beauty, pronounced gently and softly. Back home, it fits easily in people’s mouths, and today, it holds the stories my family brought with them across the Atlantic Ocean. But when I immigrated to the United States, I learned almost immediately that none of this mattered.

Here, my name wasn’t a representation of heritage or history. Instead, it was a problem to be solved. Teachers paused at it. Classmates giggled when they first heard it. Substitutes gave up before they even tried. Four letters somehow turned into a linguistic obstacle course. I grew tired of hearing the same sentences over and over: “I thought you were a boy when I first heard your name,” “I’m going to butcher this,” and “How do you say your name? Can you repeat it one more time?”

My younger brother, whose name is double the length of mine (eight letters long, filled with sounds far more foreign to the American ear), solved his version of this problem in a way I couldn’t. In kindergarten, he was given the option to choose a nickname for himself. Too young to decide for himself and unable to understand a word of English, my brother left the decision to my parents. They decided to choose a quick and easy name that people could latch onto—something more “American” that would help him fit in: “Sam.” People stopped tripping over his real name, and the nickname stuck. It liberated him, becoming a part of his identity.

Unlike my brother, I never had that option, and jealousy filled my heart every time my name was mispronounced. I desperately wished to have an American name that was easy to pronounce, but I quickly found out that there is no obvious nickname for Rano—nothing that fits, nothing that feels like me, nothing that doesn’t erase the shape of the original.

As the years went on, the disconnect between what my name meant and how it was treated became impossible to ignore. A name that was meant to represent identity, belonging, and origin was reduced to an inconvenience. My frustrations grew when names that were triple the length of mine were pronounced effortlessly, simply because they were American or white—familiar, recognizable, names that were automatically accepted as “normal.” Meanwhile, ethnic names like mine were labeled confusing or “too hard,” and the four letters I kept close to my heart remained a challenge.

On the first day of seventh grade, as my new English teacher called out names from the attendance sheet, she hesitated and paused. In response to her hesitation, my classmates immediately called out, “It’s Rah-no!” At that moment, I appreciated that my classmates knew my name well enough to help. But in hindsight, it saddens me that this pause was so predictable that my name had already been marked as the difficult one before it was even spoken.

That same year, I was assigned a new science teacher. This new teacher was kind to me from the start, but she was never able to pronounce my name correctly. She would ironically get infuriated when someone accidentally mispronounced her last name, even though she spent years consistently mispronouncing mine. For the next two years, she called me “Rona” or “Rowa,” even after countless corrections. Eventually, I gave up. This was my introduction to double standards—I had spent years patiently correcting teachers and classmates, explaining the pronunciation of my four-letter name and enduring the subtle ways it was dismissed, while she expected immediate respect for her own.

Over time, I stopped reacting when someone mispronounced it, not because it stopped hurting, but because I learned to expect it. I stopped bracing myself for the pause during attendance, knowing it would come every time. Still, I also never stopped the hope that the meaning of my name—the one it holds back home—could exist here too, fully recognized and respected.

Though I had been dealing with these forms of overcompensation for the majority of my life, when freshman year started, I discovered something that would forever change my perspective on my name: a single forgotten apostrophe. One evening, my family and I were sitting down watching a movie from my country, and my brother suddenly pointed out that a character in the movie had the same name as me, though it was spelled slightly differently—Ra’no instead of Rano. After finishing the movie, I sat down with my mom and asked why the character had an apostrophe in her name. My mom, who was a bit shocked, looked at me and said, “Your name also has an apostrophe in it.”

I was taken aback. Growing up, I had always been Rano; every test I took and every assignment I turned in were all labeled Rano. Seeing my confused face, my mom retrieved my birth certificate. To my surprise, she was right—I was indeed Ra’no with an apostrophe.

After questioning why no one had ever told me this, my mom explained that she simply didn’t think it was important. When we first started the immigration process, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) sent my green card without an apostrophe in my name. When my parents called USCIS and questioned why, they explained that the apostrophe in my name didn’t align with the meaning of the English apostrophe and therefore had to be removed to prevent confusion. My parents, who were also new to English, simply agreed and went about their day. In the English language, an apostrophe is a punctuation mark used to indicate possession or the omission of letters and numbers. In Uzbek, an apostrophe represents a short pause in a word. The use of an apostrophe in Uzbek names is common, mine being one of them.

From that moment on, every official document, paper, and passport said Rano instead of Ra’no.

Although it’s just one punctuation mark, it still hurt my heart. I had spent my whole life spelling my name incorrectly because others deemed it too complicated to be spelled properly. Though I never received a more “American name” like my brother, my name had still been changed—even in this small, almost invisible way. Every time I wrote Rano without the apostrophe, it felt like a small erasure of who I am.

For years, I had gone through disrespect and dismissal for my name, just to be incorrect myself. That tiny apostrophe was not just a paper mark—it was a symbol of my cultural identity, a subtle but powerful link to my language, my homeland, and the traditions I had carried with me, even after leaving everything familiar behind. Understanding the significance of the apostrophe in my name, I began to feel empowered by my name, rather than burdened by it. I began to understand that, even if the world around me had simplified my name, the true version had always existed, quietly preserving its meaning. Finally, I saw my name as more than just four letters that others mispronounced—it was a vessel carrying the thousands of years of history of my family, the language and customs of my culture, and the legacy of hundreds of brave, strong women I am proud to call my ancestors who carried this name before me.

From that moment on, I approached my name differently in daily life. When introducing myself to new classmates or teachers, I corrected mispronunciations with a quiet confidence I had never felt before. I no longer hesitated to say my name or wished it were simpler—I shared it proudly, sometimes even explaining its origin and meaning. I noticed the change in how I carried myself: each introduction became a small act of asserting my identity, a faint reminder that my name—and everything it represents—deserves respect.

For the first time, I stopped envying my brother for having an American nickname. Instead, I felt a pang of sympathy for him. His beautiful ethnic name had been shortened, simplified, and largely erased to fit in, while mine managed to survive. I loved that my name tells a story: of a mystical flower, of elegance, of a homeland. I felt grateful that my identity had remained intact and that my relationship to my heritage was still represented in a single name. I felt grateful that, although a little part of my name had been erased, it still existed now forever in my mind. Although I still write Rano on tests and assignments to not stir confusion between my friends, peers, and teachers, and because that had served me well for the first nine years of my life in the U.S., deep inside, I know that culturally, and to my family, I will always be Ra’no.

Growing up, I had heard the story of how I was named several times. My grandfather had asked my uncle to choose a name for me, and my uncle, who had always loved the name Ra’no, chose it for me. Every time I heard this story as a child, I was upset and took it for granted. I would put on a polite smile to not upset my elders, and wished deep inside that my uncle had named me something more internationally friendly. Now, however, knowing that my name was chosen with care and love—and that it carries the admiration of my family—fills me with pride.

Today, even when someone pronounces my name incorrectly or stumbles over it, I carry it proudly. It is more than letters—it is a celebration of the land that raised me. I no longer see my name as a hurdle; I see it as a gift, a badge of resilience, and a symbol of life.