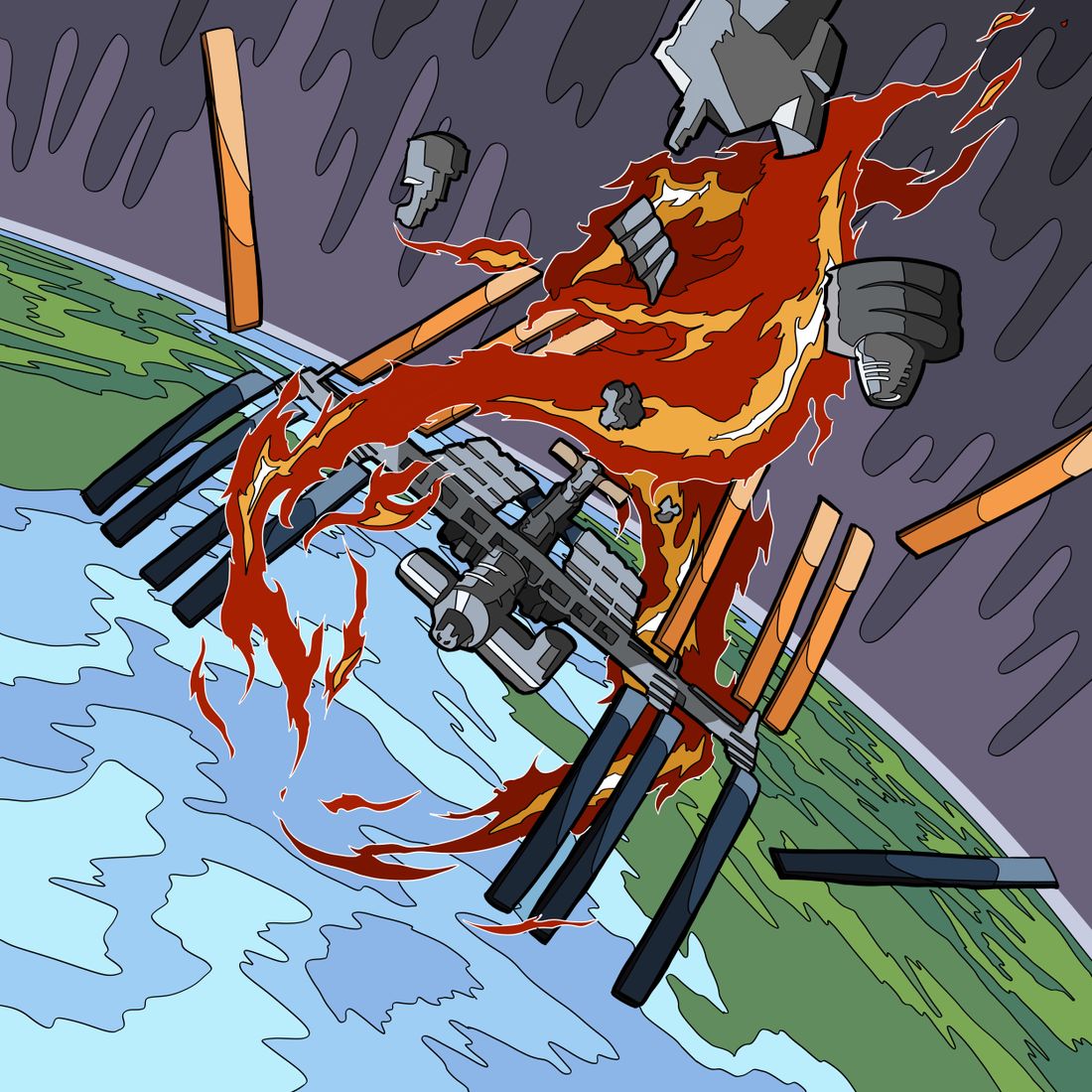

The Final Burn: Decommissioning the International Space Station

Plagued by structural decay and unsustainable costs, the aging ISS presents an enormous engineering challenge to scientists and engineers aiming to safely deorbit the station.

Reading Time: 4 minutes

For more than 27 years, the International Space Station (ISS) has served as humanity’s home in space. Its long career is finally coming to an end, with a planned retirement date set for 2030. This decommissioning is more than just the loss of another spacecraft: it signifies the end of low-Earth orbit habitation under government leadership. Born from a partnership between the United States, Russia, Europe, Japan, and Canada, the station served as the home of over 290 astronauts from 26 different countries. Now, as that chapter closes, the ISS cannot simply be abandoned. In order to prevent floating space junk and protect people on Earth, it must be removed actively and precisely.

The ISS is slowly succumbing to the unforgiving environment of space. Orbiting Earth every 90 minutes, the station fluctuates in temperature, going from searing sunlight (at 120°C) to freezing shadows (at -120°C). As the body of the station heats up, its atoms vibrate violently and push each other apart. When it cools, the atoms settle down, and the body contracts. This repeated thermal cycle of expansion and contraction causes the metal structure to experience repetitive physical stress, pushing atoms in the metal structure out of place, ultimately leading to fractures and micro-cracks that expand over time.

These physical scars are becoming critical. Persistent air leaks in the Russian PrK module (a transfer tunnel between the ISS and docked spacecraft) are worsening, and the station’s primary systems are now artifacts compared to modern technology. For example, the thermal control system’s aging radiators have not been replaced since the creation of the ISS. The deterioration of these systems poses a critical threat to the ISS and the crew, as they are fundamental to maintaining life support and cooling the sensitive computer and guidance equipment that keeps the station running. Furthermore, maintenance costs are skyrocketing as manufacturers stop producing the older electronics and hardware that the ISS relies on. The constantly deteriorating structure and increasing reliance on costly, obsolete parts make preserving the ISS unsustainable. In light of these escalating expenses, NASA has prioritized redirecting its budget towards the next giant leap for mankind: the Artemis missions to the Moon and Mars.

Bringing the ISS back down is an enormous engineering challenge. Typically, the procedure for decommissioning a satellite is a matter of gravity and friction. As a satellite falls through the Earth’s atmosphere, it collides with increasingly denser air, creating heat and friction that ultimately disintegrate the satellite. However, the ISS weighs around 450,000 kg. Unlike small satellites, the ISS is too large to burn up completely during reentry. Its high mass-to-surface-area ratio means its dense, heat-resistant core components—some the size of a car—are protected from the extreme heat and would survive reentry, presenting a hazard to anyone below.

Because of this risk, the descent must be orchestrated with extreme precision. The challenges start at the beginning of the station’s final descent: if the station enters the atmosphere at the wrong angle, it could skip off the atmosphere like a stone on water or tumble uncontrollably. A tumbling station could break apart too early, spreading debris over populated landmasses. Adding to the challenge, debris must fall in the South Pacific Oceanic Uninhabited Area, also known as Point Nemo, the furthest point on Earth from any land. While the target may seem vast, the footprint of crashing debris will stretch for thousands of miles, leaving little margin of error.

NASA has commissioned SpaceX to construct the United States Deorbit Vehicle (USDV) to safely deorbit the ISS. This spacecraft is a modified version of SpaceX’s Cargo Dragon spacecraft with a larger trunk and 46 Draco thrusters—four times the power of the unmodified version—making it perfect to perform powerful yet precise adjustments to the ISS’s final descent. The USDV will dock to the station and force it into the atmosphere with a final, high-power burn.

Environmentally hazardous materials on the ISS, such as ammonia coolant or residual hydrazine fuel, will be vaporized during reentry, reducing the risk of ocean pollution from these chemicals. On the other hand, the combustion of the aluminum structure of the ISS may release a plume of chemicals into the upper atmosphere, which may contribute to localized atmospheric changes and ozone depletion. While the specific impact of the deorbiting process remains a subject of intense scrutiny, no substantial long-term environmental effects are expected.

While the International Space Station’s fiery finale marks the end of an era, it does not mean the end of humanity’s exploration of space. Commercial companies are taking many different approaches to expand the frontiers of space. Axiom Space is currently constructing modules that will attach to the ISS, later detaching to form a free-flying station. Competitors like Blue Origin and Starlab are also designing their own independent stations equipped to host tourists, researchers, and manufacturers. While the future of space exploration is not set in stone, we can be sure that there will be no gap in our presence among the stars.